Mohammed Ibrahim’s Stolen Year

The newly freed sixteen-year-old Palestinian American shares his first account of 9½ months in Israeli military detention.

Sixteen-year-old Mohammed Ibrahim told me he was hungry every minute of every day during his nine and a half months in Israeli military detention. The pain in his head and stomach was so constant he couldn’t sleep, though that would have been difficult anyway under fluorescent lights left on twenty-four-seven. He shared a six-person cell with ten other boys, ages fifteen to seventeen, and some of them moaned and cried all night.

Still, one day boredom overtook hunger. The boys saved scraps of bread from their meals, mixed them with water, and shaped them into chess pieces. They scratched a board into the concrete floor, set the pieces out to dry, and within a few days had a complete set. Mohammed told me he played three matches and won all three. The fun lasted about a day before they were caught.

Guards stormed the cell, filled it with pepper spray, beat the boys with sticks and shields, and confiscated the chess set. They were left choking and crying on the floor, as they often were, with nothing to flush the chemicals from their eyes. It burned everywhere, especially on their scabies, which for many had turned into infected, open sores. The guards also took their mattresses, so they’d be sleeping on bare metal bedframes again. Similar punishments followed when they made playing cards from the cardboard of toilet paper rolls. Or when they did pushups. Or sang. Or laughed. The boys in Israeli military detention are forbidden from being boys.

Three weeks after Mohammed was freed, I went fishing with him in Florida. I’d spent five months covering his detention and the fight to free him, and his family asked me to come down and be with them during his first week back in the States, a return he’d made many times before. Mohammed is a dual citizen who’s split his childhood between Florida and the West Bank.

We were standing on a dock at the edge of a pond, using rickety fishing poles and cheap lures we’d found inside the rental his father had booked to house some family friends visiting from Birzeit. Mohammed’s feet and ankles were caked with mud. Earlier, we’d gone kayaking. He wanted to look for gators, so we paddled into lagoons and through thick marshes, following bubble trails and leaping fish. We found none, so we decided to race back, but Mohammed’s arms grew tired, and he was feeling mischievous. He pulled up behind me and tethered his kayak to mine so I could tow him in while he lay back, grinning. When we got back to the dock, he grabbed a rod and paddled back out, but sheepishly returned when he was ready to admit he needed to be taught how to cast.

Soon, he announced he was bored. Maybe after three casts. I told him fishing took patience. He shrugged. “I want something fast.” His father caught a small bass, and when he tossed it back, Mohammed raced in after it to scoop it out of the water and hold it up as if it were his own. We put the rods away and went swimming in the pool. At first, he kept his shirt on, embarrassed at how skinny he’d become. We teased him, and he took it off. We propped a pool net against the barbecue and turned it into a basketball hoop. I threw him alley-oops as he jumped in again and again, slamming the ball home. He is, unmistakably, a sixteen-year-old boy.

Mohammed told me that on February 16, the night he was abducted from his home in Al-Mazra’a ash-Sharqiya, soldiers blindfolded and zip-tied him, threw him face down onto the metal floor of a military jeep, then kicked him with heavy boots and beat him with their rifles as they drove. It was around 3 a.m., and he didn’t know where they were taking him. They arrived at a military compound—later identified as Ofer army camp—where he said he was pulled from the vehicle and forced to sit on the ground, still blindfolded and zip-tied, while soldiers continued to beat him on his head and all over his body. He had no shoes or socks. From there, he was frogmarched across sharp rocks to the police station a few hundred meters away.

They pulled his blindfold down and put him in a chair. He asked to speak to his parents and they refused. He was never offered a lawyer. It was freezing in the room, he said, and he had no coat. Across a table, two masked men with machine guns accused him of throwing stones at an Israeli car. He denied it. He told me the interrogator threatened that if he didn’t confess, he would instruct the soldiers to beat him again. Eventually, Mohammed said, he broke. “I couldn’t handle it anymore,” he told me. He admitted to throwing a stone, which he maintains he didn’t do, but not to hitting anything. When it was over, he said he couldn’t walk and was dragged into a holding cell, where he would remain for the next several weeks.

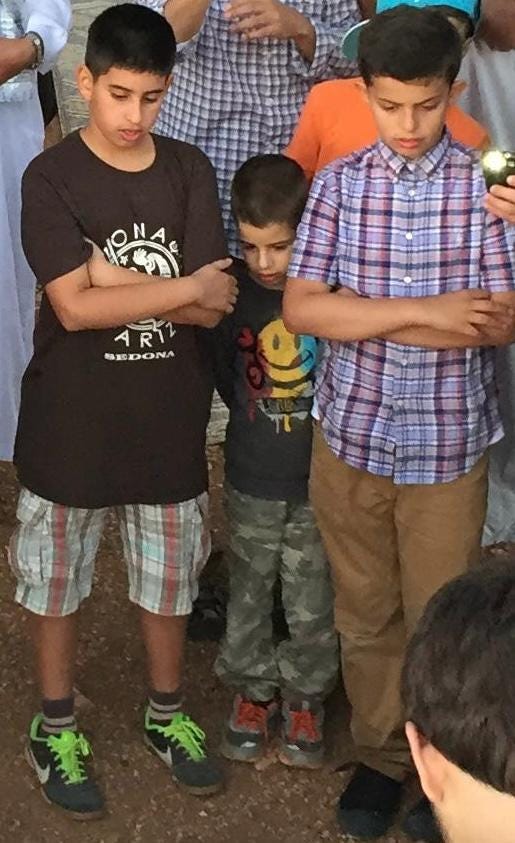

Even before all this, Mohammed was small for his age; now, months of malnutrition in prison may have permanently stunted his growth. He tries to make himself look taller when his photo is taken, standing on his tiptoes or on stacked soda cases. He won’t smile for the camera—the teenage-boy thing again—but it comes naturally, so in many photos you can see him biting his cheeks. The only way to capture him smiling is to sneak a video when he thinks you’re taking a photo, then pull a screenshot from the moment before or after. He didn’t like the photos his family chose to share as part of the campaign to free him. “I look like a baby,” he says. He still does, but it’s true: his face was chubbier then. He showed me a picture of himself standing in front of a sports car with his arms crossed, where his shoulders look bigger. Why couldn’t they have used that one? he wonders. He still has scabies rashes on his arms and legs.

During his detention, his father often described him in interviews by saying, “He’s a kid that’s impossible to dislike.” I didn’t understand it until I met him. I’ve met a lot of young Palestinian men, and many seem older than they are; they’ve been through it, and it shows. They are rough, scarred. But not Mohammed. He comes off like a boy. Somehow still has his innocence. He makes strong, open eye contact. He cannot sit still, cannot hold back his smile, even when he tries to be serious. He leapt out of his seat when I showed him a card trick, demanding to know how I’d done it. Above all, Mohammed is gentle. To spend time with him is to want to protect him—and to feel rage at what was done to him.

On March 10, Mohammed was transferred to Megiddo, a military detention center that B’Tselem, an Israeli human rights organization, has described as part of a “network of torture camps.” (“When we got off the bus,” one detainee told B’Tselem, “a soldier said to us, ‘Welcome to hell.’”) The severe overcrowding was the result of policies overseen by National Security Minister Itamar Ben Gvir, who has boasted about making conditions significantly worse for Palestinian prisoners. At the moment, Ben Gvir is leading a push to legalize the death penalty for Palestinians convicted of terrorism offenses, a category defined broadly under Israeli law, and has signaled his support by wearing a gold noose pin—closely resembling the yellow hostage ribbon—on his lapel.

In Mohammed’s cell, two surveillance cameras hung from the ceiling. An Israeli flag was mounted on the wall. The toilet was just a hole in the corner; they propped one of their paper-thin mattress upright for privacy. Some had bedframes, others were on the floor. A large, barred window looked straight onto a wall. The cell was stifling in the summer and frigid in the winter. There was no sunlight, just the blinding artificial light all day and night. There was no clock; the only marker of time was the daily wake-up at 4 a.m., when guards shone flashlights into their eyes, banged on the bars, and forced them to line up on their knees to be counted. (Mohammed, now, can count to eleven in Hebrew.) Each day, the boys were allowed out of the cell once, for between ten and forty minutes, to shower or go to the yard. The yard had no basketball hoop, no balls, no recreational equipment. Nothing at all.

The boys weren’t given individual plates, just a platter to split, but Mohammed told me no one ever tried to take more than their share. For breakfast, bread and a small bowl of labneh. Lunch and dinner were rice. Sometimes, hummus, tahini, beans, or a small sausage, if they were lucky. Occasionally, a cucumber or tomato to divide among eleven boys, cut with a plastic spoon. No fruit. They all craved sweets, but none were ever given, so they chewed dried-up toothpaste like gum. Mohammed was embarrassed to tell me this, afraid people would laugh. (I assured him they would not.) One small tube was given to the boys to share each week. On March 13, three days into his detention at Megiddo, his sixteenth birthday came and went without him realizing. When the others found out days later, they made him a cake with bread and tahini.

One of his cellmates—17-year-old Walid Ahmad, whom he quickly grew close to—was visibly sicker and weaker than the others when Mohammed arrived. Skin and bones, Mohammed told me. He had severe diarrhea, couldn’t keep food down, and shivered constantly. His skin was covered in scabies, which was ripping through the prison, leaving all the boys infested and scratching themselves raw. The boys worried about Walid, begged the guards to let him see a doctor. They refused.

On March 22, twelve days after Mohammed arrived at the prison, Walid collapsed during their daily trip outside the cell, falling face-first and splitting open the bridge of his nose. A pool of blood formed around him. The boys rushed to help and were pepper-sprayed. Mohammed said Walid remained conscious for about two minutes, looking around, scared, before losing consciousness again. A guard then arrived and dragged Walid’s motionless body across the floor by his hair.

Four days later, the boys learned that Walid, who was never charged with a crime, was dead. Back home, Mohammed’s family heard that a teenage boy had died in Megiddo and spent an entire, unbearable day trying to determine whether it was him; instead, they learned it was a boy from a neighboring town. An Israeli surgeon who observed Walid’s autopsy reported that the 17-year-old showed signs of prolonged starvation—extreme weight loss and muscle wasting—along with untreated colitis and scabies. A prison medical report also revealed that he had complained to the prison about inadequate food since at least December. His body has still not been returned to his family.

Months later, in September, Israel’s Supreme Court ruled that the state was failing to provide adequate food to Palestinian prisoners, and that it was legally obligated to provide them with enough nutrition to ensure “a basic level of existence.” Ben Gvir accused the judges of “defending terrorists” and said that the minimal food provisions he ordered would remain unchanged.

My mother joined us in Florida on Wednesday. For months, she’d been calling her representatives daily to demand Mohammed’s release, and she felt deeply connected to him and his family. When she arrived around eleven in the morning, Mohammed was clearly just waking up. But he registered who was at the door, and his eyes lit up, his face softened, and he stepped forward to hug her.

We exchanged gifts and played with the kids, drank coffee and ate sweets. Mohammed’s mom, Mona, brought out baklava; my mom had brought rugelach she’d made from my great-grandmother’s recipe. Mohammed and I slipped away to do a quick workout—push-ups, pull-ups, planks—before heading outside to play a makeshift game of HORSE, throwing a tennis ball against a stop sign. Inside, our mothers talked for a long time. Later, my mom told me that Mona said she cried every night, imagining what might be happening to her son. The helplessness was suffocating: she was desperate to touch him, to comfort him, to tell him it would be okay. The horror and dread Mona described, my mom said, were indistinguishable from what she would have felt if it had been me.

More of Mohammed’s extended family joined us, including his new cousins, seven-month-old twins, whose faces he stared into endlessly.

At dinner, while the men argued over the check, each insisting they’d cover it, a woman from another table quietly paid the bill. She was a local Palestinian American doctor. She recognized Mohammed, my mother, and me, and told us she had been calling her representatives every single day to fight for his release. Her voice was shaking as she spoke to us. She hugged Mohammed. It was very tender. He doesn’t seem to know what to make of his sudden visibility, but you can see he’s drawn toward people who make him feel safe.

Mohammed doesn’t really want to talk about his time in jail. He’d rather play soccer or chess. (When we played, he pulled out a chess app on his phone to use as a clock; I ran out of time, he gave me extra, and still beat me.) He’d rather work behind the counter at the family’s ice cream shop, where he packs so much into each cone that it feels like lead in your hand. He takes the work seriously—asking lots of questions, rinsing the scoops, quickly restocking flavors and toppings as they run low.

He was supposed to work there this past summer, training under his cousin Sayfollah Musallet, who owned the shop with another cousin. But Sayf, 20, was murdered by settlers on June 11, while Mohammed was in prison. He doesn’t know the details yet: that his cousin was beaten to death on his own land, where they used to pick olives and have family barbecues; that IDF soldiers blocked ambulances from reaching him for two and a half hours as he struggled to breathe. I tried to ask him about Sayf—twice—but his eyes turned glassy, and he shook his head. It was the only thing he wouldn’t talk about.

After Sayf died, Ambassador Mike Huckabee visited his father, Kamel, at his home. Kamel invited Zaher, Mohammed’s father, to join the meeting so they could plead for help. “They took my son away,” Kamel said to Huckabee. “We can do nothing about that. But can you give us something back, give us some happiness back? Can you at least get Mohammed out of jail?” Huckabee pledged to help, but Mohammed didn’t receive his next consular visit for another three weeks. (His first came about six weeks after his arrest.) They didn’t hear from Huckabee again until the day Mohammed was released in November, when he called Zaher to apologize for how long it took. (Kamel says he has not heard from him since that meeting, after which Huckabee publicly demanded accountability for what he called a “criminal and terrorist act.” Six months later, no one has been arrested for the killing of Sayf, though Kamel and other locals say they are certain of the identity of at least one of the settlers involved—a man who, they say, continues to roam the olive fields with a machine gun, threatening Palestinians.)

Mohammed told me that roughly every two weeks, guards carried out random searches, beating the boys and frightening them with large, ferocious dogs. Arms, legs, and ribs were routinely broken. Mohammed injured his shoulder once, and it took two months to regain full mobility. He remembers seeing the treads of thick-soled boots coming down on his head. Guards frequently pepper-sprayed the cell; on four or five occasions, they sprayed him directly in the face. Once, he said, because he was laughing.

The only news they had from the outside world came from new prisoners coming in. Or, on one occasion, when rockets from Iran soared over the prison. So the boys knew nothing about their own families. They were forbidden from ever communicating with them; Israel has said that preventing its child prisoners from speaking with their parents is a matter of national security. (Using the same justification, Israel has banned Red Cross visits to prisoners since October 7, in direct violation of international law.) Mohammed told me he dreamed about his family every night, and in his nightmares, something terrible had happened to them. He was afraid he would be released and find they were gone.

We stayed out late every night at a kava café next to the ice cream shop, also owned by the family. There was a revolving door of Palestinian American relatives and friends, friends of friends, many from the same West Bank village, Al-Mazra’a ash-Sharqiya. They showed up straight from school or work, in sweaty gym clothes after pickleball, there to see Mohammed and to sit and talk endlessly. The hospitality is too much. These people are relentless. Maqluba, shawarma, hummus. Knafeh, ma’amoul. Pizza, waffles, ice cream. They won’t take no for an answer. It never ends. I calculated that I ate roughly forty-five servings of ice cream that week alone—three ice creams a day, three servings each, for five days. We drank coffee until midnight, played poker, went back to the house around two. As I brushed my teeth, they brewed another pot.

One evening, we drove out to a ranch owned by three brothers from the extended family. The men went out to a range and shot guns. After my time in the West Bank, it was jarring to see Palestinians with guns. It all felt illicit, like a drone might take us out. But here, they are Florida men.

They had two ATVs, and Mohammed couldn’t stay off them. He tore around the property for three hours, stopping only for dinner, meat sajiyeh with tomatoes, cooked over an open fire by his uncle Zeyad. It was, frankly, loud and annoying, but no one had the heart to stop him. “You can’t make up for everything in one night,” Zeyad told Mohammed when he drove by for a snack. He laughed and kept going. I went along for a joyride and bailed when I realized he was trying to break the sound barrier. When he finally joined us by the fire, he tried to chop wood, couldn’t free the axe after the first swing, dropped it, and moved on. He picked up a giant log we’d been using as a seat and tossed it into the fire, toppling the carefully stacked pile. A small transgression; everyone groaned, then a cousin rebuilt the fire without comment. We sat around drinking coffee and talking. About family, business, politics, Israel-Palestine. Their views are all over the map—something to unpack another time. A ten-year-old explained the Big Bang to me.

One of the visiting friends was a musician and composer, Rami Washaha, who teaches at the Edward Said Music Conservatory in Birzeit. His brother was shot dead by Israeli soldiers four years earlier. He lugged a violin, an oud, and an olivewood recorder with him, providing a soundtrack of traditional Palestinian and Arab music. The younger boys danced dabke. Mohammed feigned interest for a few minutes before heading back out to the ATVs.

We ate ice cream and said our goodbyes. They all kissed Mohammed on the head. He fell asleep instantly on the drive back home.

After five months, Mohammed was transferred from Megiddo to Ofer prison. He’d still not had a trial, and each time he showed up for a hearing, he was told it was delayed. Once, he waved at the security camera, hoping his family might see it, and a guard slapped his hand down. They’d never presented any evidence against him, nor accused him of causing harm. He was allowed two lawyer visits in nine and a half months, and they had no answers. He thought he’d be in jail for years.

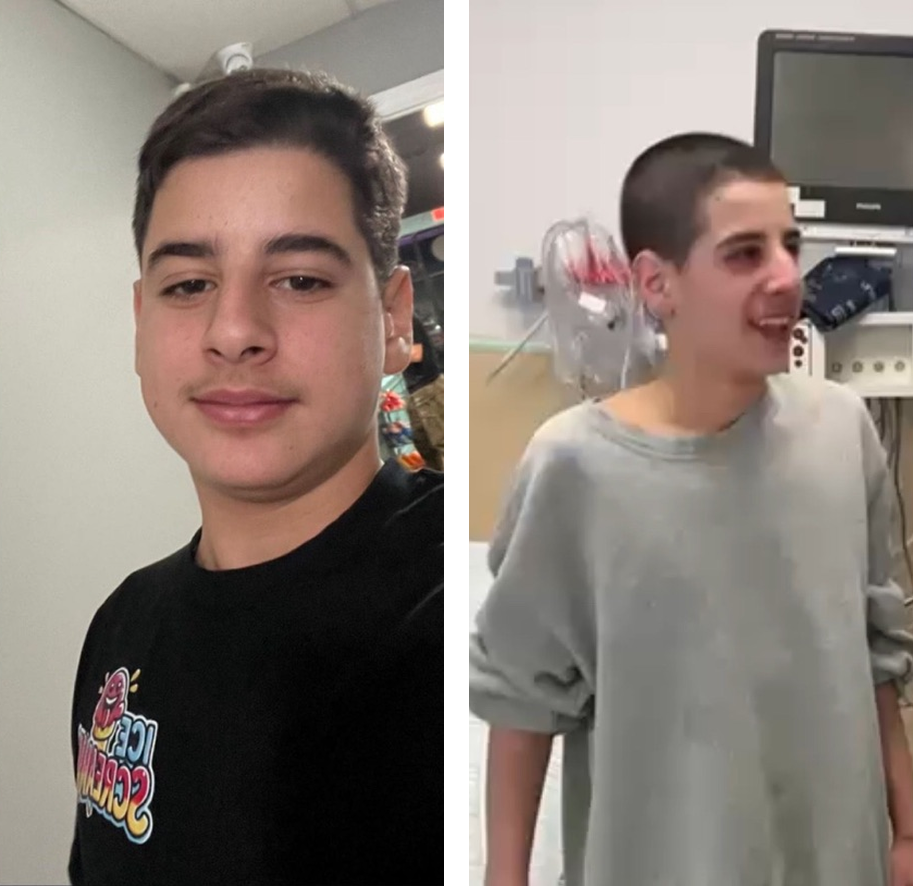

Conditions at Ofer were even worse, and Mohammed’s health deteriorated. His entire body was covered in scabies. It was worst around his groin. He had lost nearly a third of his body weight. At one point, he became so sick he couldn’t eat or get out of bed. He was allowed to see a prison doctor, who he said accused him of lying and offered no treatment. (Mohammed was treated for scabies once during his imprisonment; with no follow-up care, he says, it never went away.) For the first time, he told me, he was afraid he might die.

Outside the prison, the grassroots campaign to free Mohammed was picking up steam. Thousands of people were calling their lawmakers daily, and lawmakers were in turn pressuring the U.S. Embassy to intervene. After Zeyad traveled to D.C. in September with a delegation of American families whose relatives were killed or abducted by Israeli settlers and soldiers, the embassy assigned Mohammed’s case to an official, Mark Marrano, whom the family says became their first consistent interlocutor. He visited Mohammed in prison and reported his worsening physical and mental health to the family. (Mohammed told me that each time embassy officials came, guards threatened to beat him if he made them “look bad.”)

When news of his condition became public and lawmakers began expressing outrage, the Israeli embassy in Washington circulated a memo on Capitol Hill full of misinformation, including about Mohammed’s health. Netanyahu’s office put out a statement accusing Mohammed of committing “a serious potentially deadly crime,” claiming it was a criminal rather than diplomatic matter. The memo and statement backfired, further angering lawmakers and intensifying pressure for his release.

On November 27th, a guard told Mohammed he was due in court. But he knew his next hearing wasn’t scheduled until mid-December, so he thought they might have been mistaken. It turns out, a new lawyer had secured a deal for him, almost certainly made possible by sustained outside pressure. Mohammed had become a giant headache for the Israeli government, and they were ready to get rid of it. When they told him he would be released, he thought it was a cruel trick.

He was sent back to the cell and told he would be released in two hours. He still didn’t believe it, but to be safe, he said goodbye to the others. They gave him their families’ home addresses so he could visit and assure them their children were all right, but he had no pen or paper, so he tried to memorize them. Then guards pulled him out, put him in a car, and drove him beyond the prison gates, where his father was waiting. Mohammed told me he thought he might have been dreaming. He kept asking his father if it was real.

His father was euphoric but alarmed by his son’s emaciated state, and drove him straight to the hospital. On the way, he told Mohammed that his cousin Sayfollah had been killed. His nightmare had come true. Mohammed couldn’t breathe, and his father had to pull the car over to help him calm down. At the hospital, he was reunited with the rest of his family, including his uncle Kamel, Sayfollah’s father. For Kamel, Mohammed’s return brought tremendous joy, but watching his nephew absorb the news of Sayfollah’s death felt like losing his son all over again.

In the days that followed, the only times Mohammed left the house were to visit Sayf’s grave with Kamel, and to see the families of the prisoners whose addresses he had managed to remember. Two days after his own release, Mohammed’s three friends who had been arrested alongside him were freed as part of an extension of the same deal.

Mohammed seems to be recovering quite well. After a week of struggling to eat, he is now ravenous and has begun to put weight back on. They are indoctrinating him in their pickleball obsession. He is happy, eager to resume something like the life he had before his imprisonment. For Palestinians, this kind of rupture is grimly routine. No family has been spared from Israel’s brutality. Their suffering is ordinary and human. So is the anger, visibly smoldering in some as Mohammed described his treatment in prison. But the resilience is learned, passed down, and continually reforged. Mohammed has absorbed from his family and loved ones that he has to feel the pain and then go on with his life. “Just look at Gaza,” they often say. “What choice do they have?”

The family faces difficult decisions. Mohammed missed a full year of school. For now, they are letting him rest, play, and ease back into normal routines. Trauma, of course, takes many forms, and he is not out of the woods. But soon they plan to begin homeschooling him, hoping to catch him up by the fall. They want to return to their home in the West Bank, but they are afraid. The family is known to Israeli authorities, and they worry about retaliation. Settlers have occupied their olive fields and now use the surrounding hills to launch attacks on the village itself. On Wednesday, December 24, settlers burned a home there, leaving graffiti that read, “Hello from the outskirt kids.”

At least 350 Palestinian children remain in Israeli military detention, many without charge. Mohammed believes he saw over 500. As far as we know, none of them holds American citizenship, which means they do not benefit from the kind of grassroots pressure campaign that helped secure Mohammed’s release. His family is committed to fighting to free them all. Mohammed talks about them often.

While I was in Florida, I mostly tuned out the news. But a few stories broke through. An online lynch mob doxxed and falsely accused a Palestinian American student of carrying out the Brown University shootings, with no evidence whatsoever, plunging him into what he later described as an “unimaginable nightmare.” “But it is a story every Arab, Muslim, Palestinian, and marginalized person knows all too well,” he said.

Then, in a single day, two Palestinian sixteen-year-old boys were shot dead in the West Bank, one by an Israeli soldier, one by a settler. The boy killed by soldiers was immediately branded a “terrorist” by the IDF and accused of “hurling a block” at them, an allegation offered to justify his summary execution.

Days later, a security-camera video emerged showing the eighteen seconds before the shooting. The boy walks down an alley as two Israeli soldiers crouch behind a corner. When he reaches it, one soldier raises his rifle and shoots him at point-blank range. There is no reason to believe he threw anything at all.

The Israel Prison Service and Israeli Defense Forces did not respond to requests for comment.

For more on the effort to free Mohammed, see my interview with Zeyad here.

For Kamel’s account of the simultaneous grief and joy of this moment, watch my interview with him here.

Reader Note: As many of you know, I recently took the plunge into full-time writing and reporting, leaving behind the work that paid my bills for the past fifteen years. Journalism isn’t exactly a gold mine these days—especially for those committed to holding power to account and covering what the mainstream won’t—so paid subscriptions are what make this possible.

Every bit of my reporting, including my trips to the West Bank, is self-funded. No crew, no security team—just me. This holiday season, consider upgrading to a paid account to get access to all of my work, including exclusive interviews and on-the-ground reporting. It costs just $6.67 / month for an annual subscription, or $8 month-to-month.

I was reading this at the kitchen table in my in-laws' house in Toronto over the holidays... I laughed at the part about throwing over the log you were all sitting on, and the ATVs. When I did, my 12 year old asked what it was I was laughing about, and I had to provide some context, which broke my heart... This whole piece is enraging and inspiring all at once. I'm so relieved that Mohamed is out and so horrified that all of it ever happened, and that so many children are still trapped in this torture. May they all be free and safe.

Very happy for his release, and thank you and Mohammed for sharing his story.

I had tears when I read the bit about Walid. So disgustingly routine.