Israel might annex the West Bank—what would that actually mean?

A brief explainer.

For weeks now, stories about Israel’s looming declaration of sovereignty over the West Bank have been breaking almost daily. I’ve argued—along with others—that annexation has in many ways already happened. Yet what’s actually unfolding on the ground, and what would change with a formal declaration, remains shrouded in mystery to most observers, like so much of the occupation, long buried under euphemism. This explainer is meant to get you up to speed.

Quick editor’s note: The first three sections of this explainer, as well as its conclusion, draw heavily from my June Baffler essay, The Annexation of the West Bank Is Complete—in some cases quoting passages directly. For a fuller account of how we arrived here, read that next.

What is the “occupation”?

Israel’s military occupation of the West Bank is, on paper, temporary. Under the Hague Regulations and the Fourth Geneva Convention, an occupying power must safeguard civilians, maintain public order, and hold the territory “until its status is resolved”—meaning until sovereignty is decided by a negotiated political settlement, not by unilateral acts. What’s prohibited is permanent change: transferring the occupier’s civilians into occupied land, dismantling the occupied population’s buildings and infrastructure or constructing its own, applying the occupier’s civil laws in the occupied territory, or outright annexation. This has been black-letter law since 1949.

But within hours of Israel’s conquest of the West Bank and East Jerusalem in 1967—captured from Jordan during the Six-Day War, which Israel launched with strikes on Egypt (from which it seized Gaza and Sinai) and Syria (from which it seized the Golan Heights)—the state violated these laws, demolishing Palestinian homes near East Jerusalem, expelling thousands, and breaking ground on its first settlement. From that point forward, settlement became the state’s most consistent project. By the mid-1990s, 250,000 settlers lived among 1.5 million Palestinians. Today, the number is closer to 700,000 settlers living in 141 settlements and more than 200 illegal outposts—unofficial settlements not authorized by Israel—among 2.5 million Palestinians. Under international law, every settler is there illegally.

The 1995 Oslo II Accord partition of the West Bank into Areas A, B, and C—Area A under full Palestinian civil and security control, Area B under Palestinian civil control with shared Israeli security, and Area C, about 60 percent of the land, under full Israeli control—didn’t change the fact that the land belonged to the Palestinians. Even so, the “dovish” Yitzhak Rabin never contemplated pulling settlers out, and settlement growth only accelerated.

For decades, military occupation law at least imposed procedural brakes on the settlement movement. Lawyers from the Israeli military—which, despite its brutality, didn’t share the settlers’ ideological commitments as an institution—had to review expropriations and construction, and sometimes dismantled illegal outposts or blocked plans in an effort to maintain order. That created occasional friction between the military and the settlers, who derided soldiers as “Nazis,” and provided a thin layer of insulation between Palestinians in the West Bank and the settlers’ most maximalist ambitions.

Why does the West Bank matter to the settlers?

Because it’s not the West Bank to them—it’s “Judea and Samaria,” the cradle of ancient Jewish civilization. Never mind the archaeological record, which testifies to dozens of lineages—Islamic, Christian, Jewish, and non-Abrahamic—or the Palestinian one still enduring today. In the Bible, this is the land of Jerusalem and the First and Second Temples, of the southern kingdom of Judea and the northern land of Samaria, the stage for David and Solomon, and the soil where biblical law and prophecy took root.

Gaza, by contrast, appears in the Old Testament chiefly as the domain of the Philistines—the Israelites’ eternal foe—and as a frontier of unrelenting conflict to be conquered or razed, but not inhabited.

As for Israel itself, settlers are quick to argue that if the state’s legitimacy within the 1948 borders rests on a biblical claim, then their case in the West Bank is even stronger. On that point, they’re correct.

What is the “silent annexation”?

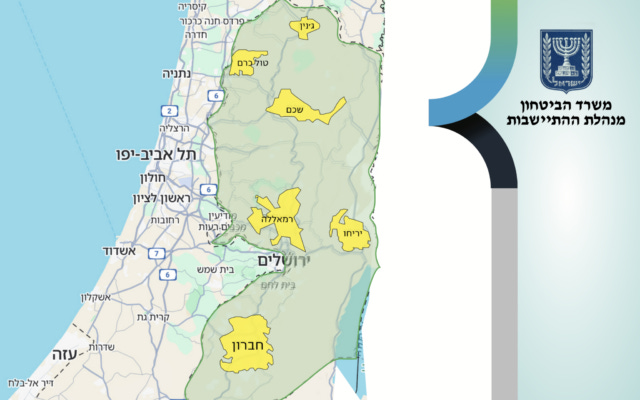

In early 2023, Netanyahu formed a coalition with far-right extremists in order to hold on to power. One of them, Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich—a settler who spent his youth building illegal outposts in the hills and calls it his life’s mission to prevent a Palestinian state—cut a deal with Defense Minister Yoav Gallant to become “Additional Minister in the Ministry of Defense,” giving him effective control over West Bank governance under the auspices of military occupation. He built a shadow government inside the ministry, the Settlement Administration, which siphoned powers from the army’s Civil Administration and handed them to settler ideologues. With the guardrails systematically eliminated, Smotrich retroactively legalized outposts, accelerated construction, and, through his finance portfolio, funneled a disproportionate share of Israel’s budget east of the Green Line. The “occupation” still existed in name, but settlers handpicked by Smotrich now held the levers of power.

October 7 provided perfect cover. Smotrich collapsed the distinction between Hamas and the Palestinian Authority—the West Bank’s ineffectual, corrupt governing body that many Palestinians call Israel’s “subcontractor”—declaring, “There is no big difference between Hamas and the Palestinian Authority. The Arabs are the same Arabs, and the land is the same land. The sea they want to throw us into is the same sea.” Netanyahu and his allies long preferred this logic: Hamas, a designated terrorist organization, was easier to delegitimize than the PA, which had inroads with the West. Smotrich put it bluntly in 2015: “The Palestinian Authority is a burden, and Hamas is an asset.” But that wasn’t just rhetoric. For decades, Israel quietly propped up Hamas—allowing Qatari money into Gaza and tolerating its rule—precisely to weaken the PA and block pressure for a Palestinian state.

This rhetorical merger of enemies enabled Smotrich to brand all Palestinian civil activity as “hostile” and justify strangling the PA. He froze over $80 million in tax revenues, starved Arab municipalities and East Jerusalem schools of funds, and, when sanctioned by the West in 2025, retaliated by canceling a financial waiver that kept billions in Palestinian-Israeli bank transfers flowing. Settler violence was also enshrined as policy: Thousands were drafted into new “Regional Defense Battalions,” issued uniforms and M16s, and unleashed on villages—raiding homes, uprooting crops, and expelling entire communities with the military and state’s backing.

Last month, the Israeli government approved construction in E1, the strategic twelve-square-kilometer corridor east of Jerusalem whose development would sever East Jerusalem from the West Bank and cut the territory into disconnected northern and southern cantons. Frozen for decades under US pressure, Smotrich finally pushed it through on the promise it would “kill the Palestinian state de facto” as European leaders lined up to recognize one.

This is the quiet annexation: hollow the Palestinian Authority from within, dismantle occupation law from without, and replace both with Israeli civil governance. As Smotrich told his followers last year, his goal was to “change the system’s DNA,” creating structural shifts that would endure “even if the government falls tomorrow”. Meanwhile, settlement building—or “facts on the ground”—makes the changes virtually irreversible. The Green Line disappears not by proclamation but by attrition.

Why hasn’t Israel formally annexed the West Bank before?

For years, formal annexation of the West Bank was a nonstarter even with Israel’s closest allies—the myth of the “peace process” and the “two-state solution” demanded it. Even the Trump administration, despite unprecedented concessions to Israel, balked in 2020 when the UAE tied normalization to freezing Netanyahu’s partial annexation plans, putting the Abraham Accords—Trump’s crown jewel—at risk and prompting Netanyahu to shelve them.

Another brake has been the citizenship problem: annex the West Bank and you inherit millions of Palestinians. Offer citizenship and you erode the Jewish majority; withhold it and apartheid is undeniable. Creeping annexation let leaders dodge that dilemma.

Hence Smotrich’s boast that the work to bring one million settlers into the West Bank was being done “quietly and without spectacle.” Netanyahu delivered the same message to settler leaders last month: Israel is deepening its “hold on the Land of Israel,” he assured them, but it’s “better to reduce the talk.”

But several new forces are now pushing toward a formal sovereignty declaration: Settlers, with more political power than ever, are making a renewed push. Israeli leaders are also now framing annexation as retaliation against European moves toward recognition of a Palestinian state, which Smotrich vows to preempt—“By September, there will be nothing left for Europe to recognize,” he said. And finally, Trump has reportedly given the green light, after Miriam Adelson pumped $100 million into his campaign on the promise that he would back West Bank annexation. On Sunday, as news broke of the Trump administration signaling its openness to annexation, Israeli President Isaac Herzog’s office announced that he would be presenting Adelson with the Presidential Medal of Honor, the state’s highest civilian honor.

So what would formal annexation actually mean?

Annexation is when a state simply declares that land beyond its borders is its own—usually after military conquest, and always without the consent of the people who live there. Russia did it with Crimea in 2014, and more recently, with Donetsk, Luhansk, Kherson, and Zaporizhzhia. International law doesn’t hedge on this point: annexation is flat-out illegal.

So what would actually change if Israel formally annexed the West Bank—or pieces of it? The last guardrails on the settlement enterprise, already splintered by Smotrich’s bureaucratic coup, could be gone in an instant. Israeli courts, zoning boards, and cross-functional ministries could extend their reach overnight. Settlement construction would kick into overdrive. All of the mechanisms of apartheid and dispossession already in action—uprooting olive trees, bulldozing homes and infrastructure, expanding outposts, arming settlers, walling in cities, strangling movement, diverting water, weaponizing heritage law, denying construction permits, etc.—would no longer be constrained by even the pretense of international law. (The effect of Israeli law on these practices remains to be seen; in fact, some settler leaders have openly opposed annexation, fearing that the formal application of Israeli law would expose their system of Jewish supremacy to legal challenge—though judicial reforms and legislation aimed at aligning state law with settler interests have gone far in easing those concerns.)

Annexation could also mean a wholesale transfer of Palestinian land into Israeli hands. Farms, agricultural land, and villages could be folded into the state—a process already kicked off in May when the Knesset approved a land registration drive in Area C, enabling Israel to claim vast areas of Palestinian-held land that were never formally registered, largely because Israel froze the process in 1968. Entire communities would be put on the chopping block for expulsion and demolition.

For precedent, we can look to Israel’s earlier annexations. East Jerusalem, seized in 1967 and formally annexed by the 1980 Jerusalem Law, was redistricted to maximize land while minimizing Palestinians—absorbing territory from 28 surrounding villages without most of their people. Overnight, Palestinians in the annexed territory were reclassified as “permanent residents” rather than citizens: no passport, no vote in national elections, movement restrictions within East Jerusalem, Israel, and the West Bank, and the constant threat of residency revocation if they traveled abroad for too long. Palestinians there can apply for Israeli citizenship through a restrictive and challenging process, with the ministry rejecting requests for reasons ranging from family land ownership in the West Bank to failed Hebrew tests. Over 14,000 Palestinians in East Jerusalem have had their residency status revoked, while only 5% have received Israeli citizenship.

Annexation also triggered waves of land seizures and settlement building: entire neighborhoods like Pisgat Ze’ev and Gilo were planted on confiscated land, fragmenting Palestinian communities and hemming them in with walls and bypass roads. At the same time, a two-tiered system was cemented. While settlers enjoyed state-of-the-art roads, schools, and utilities, Palestinian neighborhoods were chronically starved of basic services, despite their residents paying the same municipal taxes.

A year later came the annexation of the occupied Golan Heights: tens of thousands of Syrians expelled, more than a hundred villages razed, and Israeli law extended over the ruins.

What are the options on the table?

A number of options have been considered over the years. Based on the latest reporting, these three scenarios, all discussed in the past, are the least likely to be enacted:

Annexation of settlements only. Codifies what already exists: Israeli law applied to settlers wherever they live.

Annexation of the entire West Bank. Extremely costly, forces the citizenship question into the open, and would trigger enormous international backlash.

Annexation of Area C. About 60 percent of the West Bank, containing all Israeli-authorized settlements and 180,000–300,000 Palestinians.

As of last week, Netanyahu’s closest aide, Ron Dermer, indicated to American officials that this was the leading option:

Annexation of the Jordan Valley. Roughly 30 percent of the West Bank, stretching the full length of its eastern border along the Jordan River from the Dead Sea to the northern boundary, and extending westward from the river to the central highlands. This is the most fertile agricultural land in the West Bank, and home to nearly 65,000 Palestinians and 11,000 settlers. Israel already blocks Palestinians from using about 85 percent of the Valley, designating much of it as state land, military zones, or settlement jurisdictions. For the Palestinians in small rural communities, this has meant home demolitions, forced displacement for army training exercises, and constant pressure to abandon their land. Annexation would entrench Israel’s control, converting today’s patchwork of restrictions into sovereign borders. Proponents of the plan call it Israel’s “security belt,” as annexing the Jordan Valley would cut off Palestine from its border with Jordan, encircling all of its remaining territory within Israel’s new unilaterally-declared borders.

Courtesy of Al Jazeera.

But settler leaders were wholly unsatisfied with that plan, and are now pressing for a more ambitious option:

Annexation of everything except the major Palestinian population centers. Over 82 percent of the land—whether Area A, B, or C—encompassing the whole West Bank except the six major Palestinian cities.

“The principle of sovereignty is maximum land and minimum population,” Smotrich said while rolling out the plan, later telling Haaretz that the roughly 80,000 Palestinians who live in the territories expected to be annexed would receive the same status as East Jerusalem residents. “We have no desire to apply sovereignty over enemies.” In other words: Annex as much land as possible without the obligation of granting Palestinians citizenship—“effectively altering the map with minimal demographic consequences.”

He was vague about the fate of the Palestinian Authority, saying only that “the Arabs of Judea and Samaria will initially manage their affairs through the Palestinian Authority, and later without any collective framework,” adding, “If the Palestinian Authority dares to raise its head and threaten us, we will destroy it just as we are destroying Hamas.”

It’s worth noting that Jenin and Tulkarm—two of the six cities that would remain under nominal Palestinian control in the final annexation scenario, and long centers of the fragmented Palestinian armed resistance in the West Bank—have already been devastated by Israeli military campaigns over the past year, with 30,000–50,000 residents displaced. Raids have also intensified in the other four cities—including an Israeli military bank robbery in Ramallah last week, where the Palestinian Authority is based, under the pretense of seizing Hamas “terror funds.” There is every reason to believe that if such a sovereignty plan proceeds, state-backed settlers and the army will accelerate their violent campaign of ethnic cleansing in both the newly annexed areas and the Palestinian enclaves left behind, paving the way for full West Bank annexation.

For more clues to what this might mean for Palestinians, Smotrich’s 2017 Decisive Plan—often described as a blueprint for annexation—spells out three options for the “Arab population of Judea and Samaria”:

Subjugation: Palestinians willing to renounce national aspirations may remain in the land as “individuals” under Jewish sovereignty. They would be confined to municipal self-administration without national character (an expanded East Jerusalem model), granted individual rights but no collective political rights. Over time, they could apply for citizenship, contingent on loyalty, national or military service, and acceptance of the Jewish state.

Emigration: Those unwilling to relinquish their national ambitions would be encouraged—or incentivized—to leave, aided by Israeli-funded “relocation grants” to Arab states or other destinations.

Force: Anyone who continues to resist Israeli rule would be treated as a terrorist—“dealt with by the security forces with a strong hand.”

What would the blowback be?

The strongest force working against annexation today may again be the Abraham Accords. On Wednesday, the UAE warned Israel that annexation would be a “red line” that would “end the vision of regional integration.” A senior adviser to the Emirati foreign minister appealed directly to Trump’s ego: “We trust that President Trump will not allow the Abraham Accords tenet of his legacy to be tarnished, threatened or derailed by extremists and radicals.” The warning echoed a 2020 op-ed by the UAE’s ambassador to the United States in a leading Israeli paper, which framed the choice bluntly: Israelis could have annexation or normalization, but not both. That message resonated strongly with the public at the time and may have been decisive in forcing Netanyahu to back down. This morning, The Jerusalem Post reported that “the issue of applying sovereignty to the West Bank has been removed from the agenda” of Netanyahu’s meeting with top ministers and aides after the UAE’s warning.

Annexation also risks provoking an expansion of the BDS movement, as international bodies that already boycott work tied to the occupied West Bank are signaling spillover to Israel proper. A bill to transfer oversight of West Bank archaeology from the military’s Civil Administration to the Israel Antiquities Authority—widely read as creeping annexation—has drawn sharp pushback from Israeli archaeologists themselves, who warn that blurring the line “between legitimate archaeology in Israel and non-legitimate archaeology in the West Bank” could trigger academic boycotts and cause funding to dry up.

France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom issued a joint statement warning that annexation would be a “serious breach of international law,” but offered no consequences—closing instead with a reaffirmation of “Israel’s right to security” and a condemnation of “recent attacks on Israel from Gaza.” The EU is still divided on whether to impose sanctions over the genocide in Gaza, though some European states have already moved unilaterally, barring or sanctioning far-right ministers like Smotrich and Ben Gvir. If annexation proceeds, it’s possible that similar targeted measures against extremist settlers and politicians could expand—or even escalate to trade pressure, with calls already mounting to suspend the EU-Israel Association Agreement.

The UN and the International Court of Justice will almost certainly condemn any sovereignty move, as they did in July 2024 when the ICJ declared Israel’s decades-long occupation illegal and ordered it to end settlement activity, evacuate settlers, and pay reparations. But such rulings are advisory and carry no enforcement power; without states willing to back them with sanctions or diplomatic isolation, they remain symbolic.

A spokesman for PA President Mahmoud Abbas reiterated that “any annexation or settlement activity by Israel is illegitimate, condemned, and unacceptable,” though in practice the Authority’s only real move is to keep pressing for recognition at the UN—something that will be more difficult with the US banning their representatives from entering the country for the General Assembly.

The Israeli public, for its own part, is conflicted. There hasn’t been much recent polling on annexation itself, but a 2025 Pew survey found that more Israelis say continued settlement building improves their security (44%) than think it undermines it (35%). Even if opinion is mixed, the political class has been decisive: in July, the Knesset voted 71–13 in favor of a nonbinding annexation motion.

What drives Israeli attitudes above all else is security—regarding the West Bank, this is summed up in the so-called “bulletproof vest theory”: the belief that settlements and the army’s presence serve as a protective buffer against the barbarians to the east. (Settlers often boast that an October 7-type attack could never have come from the West Bank.) That logic has crowded out everything else: only 21 percent of Israelis now believe peaceful coexistence with a Palestinian state is possible, down from half in 2013, while 65 percent say they are “extremely or very concerned” about rising violence against Jews in the West Bank and East Jerusalem.

What’s next?

Unclear. Until yesterday’s UAE threat, the steady drumbeat of statements and leaks about a sovereignty declaration suggested an announcement was imminent. But money talks, and if recent history is any guide, the plan could be back on ice now that normalization is on the line. Then again, with the UN General Assembly set to meet on Palestinian statehood—without the Palestinians—on September 22, Israel may be holding its fire to align an announcement with that timing.

To close, I’ll return to the conclusion of my Baffler essay—because nothing captures the inevitability of this moment more clearly than Smotrich’s own words.

Smotrich has always understood the origin of the current propelling him. “I believe that the yearning of generations for this land, and the confidence in our ultimate return thereto, are the most profound driving forces of the progression of the Return to Zion which led to the establishment of the State of Israel,” he wrote in the 2017 Decisive Plan. On the inconvenient reality of the land’s current inhabitants, he added, “The statement that the Arab yearning for national expression in the Land of Israel cannot be ‘repressed’ is incorrect. It worked fine for the State of Israel, and it needs to work in the same way for Judea and Samaria.”

For Zionism, Smotrich knows, the formula has never changed: the founding myth will drive you forward, force will deliver the promise.

Postscript (September 5, 2025):

Yesterday, hours after I published this, Israel’s Channel 14—Netanyahu’s favorite network—reported that the military is preparing for all-out war in the West Bank in September, calling it a “sensitive month due to the UN assembly and political developments.”

The subtext isn’t hard to parse: with UN recognition of a Palestinian state on the table and annexation pressures mounting, the military is preparing for Palestinian resistance—promising to freeze Gaza operations, shift forces east, and wage “a war that will end decisively.” That choice of words, of course, echoes Smotrich’s 2017 Decisive Plan—his blueprint for annexation and for solving the Palestinian question once and for all. Settlers and right-wing extremists have long been itching for a confrontation, even a Third Intifada, as the pretext to make it a reality.

No one reports as rigorously and thoroughly as you do Jasper, very well-written as usual!

How has the West not only allowed this illegal behaviour but also enabled it all these years while still painting the Palestinians as the terrorist? It's all so heartbreaking