A Lynch Mob in the Olive Fields—and the State Behind It

Pulling at the threads of the attack in Turmus’ayya

I’ve just returned home after three weeks in the West Bank. I have more material than I know what to do with—photos, videos, audio recordings, notes, interviews—but I’m still struggling to envision how to convey the sheer terror in the olive fields this season. My first dispatch from the West Bank, nearly two years ago, was titled You Don’t Understand How Bad It Is Here. Now, I’m not sure even I fully understand what I witnessed.

In the coming weeks, I’ll be sorting through everything—organizing notes and footage, structuring timelines, following leads, connecting dots. The shape of a larger piece is starting to form in my mind, but that one will likely be for a magazine, so it may be months before it’s out. In the meantime, I’ll do my best to share shorter pieces that illuminate the unprecedented levels of violence and injustice unfolding across the West Bank.

To start, I want to pull on some threads from the incident two weeks ago, when I—and many Palestinians—came very close to being lynched by a mob of Israeli settlers.

My reporting is entirely self-funded. To help me keep bringing you the stories the mainstream media won’t, upgrade to a paid subscription at 20% off—$64 for the year or $6.40 a month.

Some Background

For years, settlers have crept closer and closer to Turmus’ayya—a relatively wealthy town outside Ramallah made up of mostly Palestinian Americans who travel back and forth between the US and the West Bank. These particularly violent settlers have splintered off from nearby settlements, including Shiloh, to establish outposts on stolen farmland, seize farmhouses, and attack Palestinians who try to reach their olive groves.

Despite the escalating violence, local farmers keep returning to their olive groves—not only for income, but for pride, and, above all, because they see it as the last line of defense before the settlers reach the village itself. In June 2023, settlers staged a pogrom in a residential neighborhood of Turmus’ayya: torching homes and cars, injuring fourteen people, and killing a young father. Locals fear this will become the new normal if they can’t hold their ground in the fields.

The past two olive harvests have been marked by violence and meager yields, carried out under the constant threat of settler attacks. This year, Turmus’ayya’s farmers decided to move as one—heading out together on Sunday, October 19, hoping that safety in numbers might hold. But a day earlier, one farmer and his son got a little too brave and went out alone. Settlers armed with farm tools descended on them almost immediately, leaving the father with deep gashes on both sides of his head, and their truck wrecked and set ablaze before they managed to escape.

On the morning of October 19, I joined the farmers. We knew there would be confrontations, but no one anticipated the scale or ferocity of what followed.

The Timeline

7:35 a.m. — Farmers meet at a central point in town and begin driving into the olive fields in a caravan. I ride with Yaser Alkam, a Palestinian American farmer and lawyer who has a home in Anaheim, California.

7:37 a.m. — The caravan is stopped by a settler standing in the road with a gun, holding it in plain sight and staring us down while speaking on his phone. Several others appear behind him. Later, I learned his name: Amishav Melet, leader of the Or Nachman outpost in Turmus’ayya’s olive fields (seen in the video above)—an infamously violent settler whose gun was once confiscated by the IDF after he shot a Palestinian, according to an Israeli police officer I spoke to. Remember his name.

The caravan turns around to find another route.

8:16 a.m. — The new route is successful. Farmers and workers disperse to their own plots of land. Right away, we find that Alkam’s trees are barren—most likely due to poor weather, rather than settlers having picked them already. He decides to head home. I plan on hitching a ride to join another farmer.

8:35 a.m. — We begin the drive out, but settlers are waiting at the top of the hill. We try another road, but an army jeep blocks the exit.

8:37 a.m. — Yaser and I decide it’s too dangerous to drive toward the jeep; Israeli soldiers are known to fire on approaching cars that don’t have yellow (Israeli) plates. Since he’s Palestinian and I’m not, we agree the safest bet is for me to walk forward with my hands raised and try to speak with the soldiers. As I approach, they aim their rifles at me—standard procedure in the occupied West Bank.

8:38 a.m. — I put my phone in my pocket, recording audio only, and explain that we’re trying to get back to Turmus’ayya, but settlers are blocking the exit. I tell them I’m American. A soldier asks if I “have family here,” likely trying to determine whether I’m an American or a Palestinian American—as in, am I a real American—a distinction that usually matters, though maybe not in this case. After questioning, they tell me they’ll provide us with safe passage out of the fields.

8:42 a.m. — I return to the car, and we drive up the hill toward the army jeep. At the top, meters away from the jeep, we find two settlers on an ATV—including Amishav Melet, the armed local leader we’d seen earlier. He is on his phone again. Nearby, a Palestinian car has its windshield smashed and tires slashed. Workers stand outside of it. I ask the soldiers if they will move the settlers. The soldiers tell Yaser and me to wait, and confirm they’ll move the settlers so we can pass.

8:44 a.m. — The army jeep suddenly speeds off over the ridge, leaving us—and the other Palestinians who have already been attacked—stranded with the settlers, including the armed Melet. You can catch a glimpse of him through the windshield in this next video.

Moments later, Melet and the other settler ride their ATV in the same direction the soldiers went and disappear. Thinking we’re in the clear, we begin to head back toward town, but quickly see the damaged car struggling. I get out to help and tell Yaser to keep driving—you can’t go very fast here, and I’ll catch up.

8:49 a.m. — While I’m helping push the damaged car, a mob of settlers suddenly pours over the ridge, hurling stones and charging toward us. I run, filming for a few seconds before putting my phone away and sprinting as fast as I can down the hill towards the village. The Palestinian driver in the damaged car, I later learned from video footage, was dragged out but managed to escape. The settlers set his car on fire.

Here’s a shot from another angle, filmed by a Palestinian across the fields. That’s me in black, running and filming.

The particularly brutal details of what happens next aren’t relevant to the new developments, so I won’t include the video again—frankly, I’ve seen it enough, and it’s already in my previous post and widely circulating online. To quickly summarize:

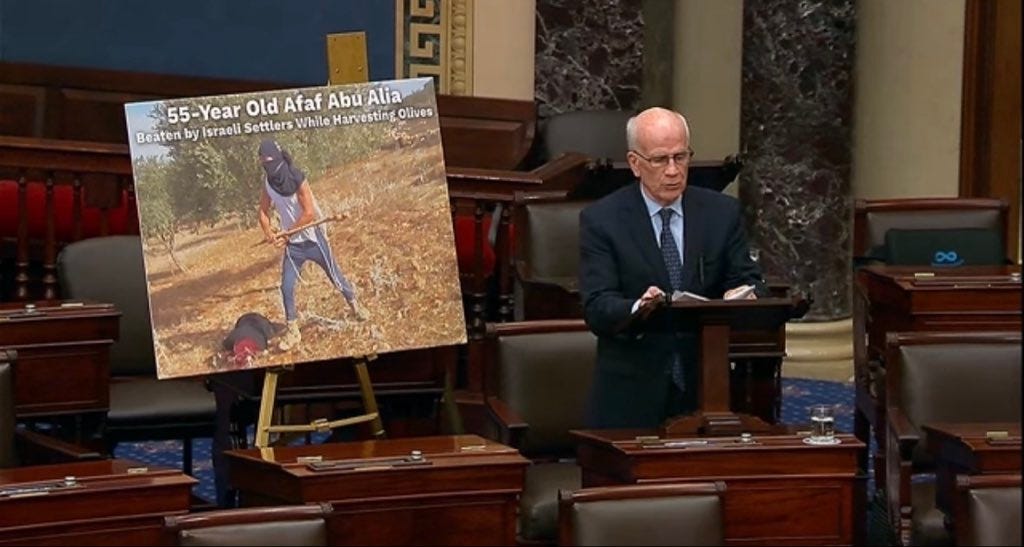

8:51 a.m. — I reach Yaser’s car, but we’re stuck in a logjam and can’t move. A masked settler carrying a club—clearly fashioned as a weapon—smashes through our rear windshield, then runs ahead and attacks a defenseless woman standing beneath an olive tree: Afaf Abu Salia, a grandmother known as Um Saleh, the sister-in-law of the man dragged from the car. (If you watch the video above closely, you can see it’s the same settler who assaulted them both.) He knocks her unconscious with the first blow, then strikes her motionless body twice more before moving on to club two activists.

8:53 a.m. — I get out of the car and reach the severely wounded Um Saleh by 8:54. She’s moaning in pain, barely conscious, blood running down her face and soaking through her hijab. Settlers are still hurling stones, and smoke from several burning cars billows into the sky. With two others, I help her into a car. Yaser picks up one of the injured activists and drives him to the hospital. He has a broken arm, broken leg, concussion, and needs staples in his head.

Over the next five to ten minutes, the settlers begin retreating up the hill as a crowd of Palestinian villagers gathers below.

The Immediate Aftermath

I stayed at the scene for over an hour after the attack, and no Israeli forces—police, military, ambulances—ever appeared. Despite this, after the video went viral, the IDF fabricated a story to the BBC and other outlets, claiming “the confrontation was dispersed after its forces arrived.” It’s a bald-faced, categorical lie.

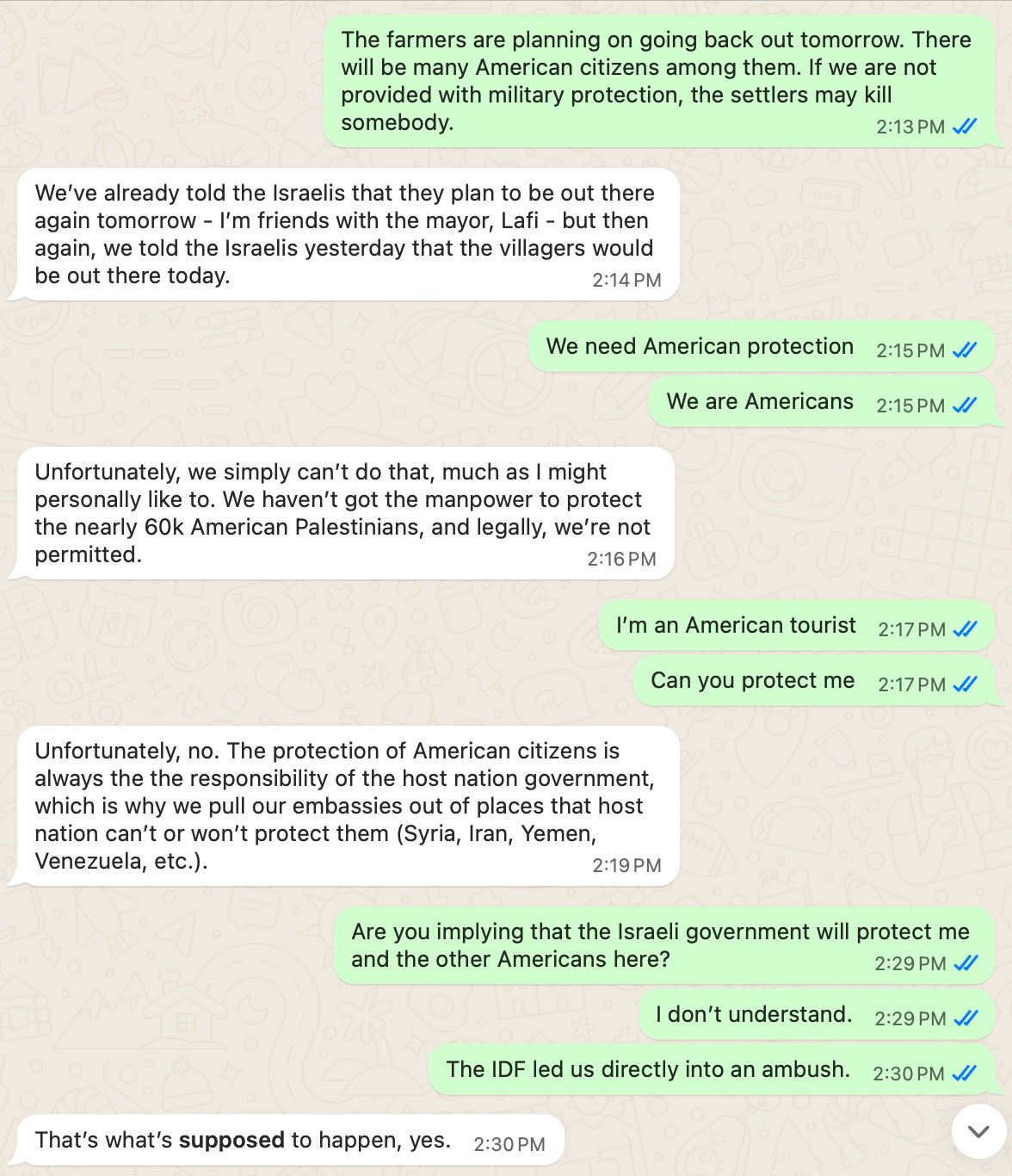

A few hours later, the US Embassy in Israel contacted me. Two senior staffers expressed outrage and sympathy and promised to follow up after internal meetings. Here is our next exchange:

Days later, when I was again in danger—this time surrounded by settlers in Duma—the same embassy officer ignored my messages.

I’ve also been ignored by my own representatives—Senator Chuck Schumer, Senator Kirsten Gillibrand, and Representative Dan Goldman—whom I’ve publicly called out in widely shared videos. They’ve ignored my mother, too—a “Jewish grandma,” as she likes to remind them on her daily calls to their offices, who’s voted for Schumer and Gillibrand for decades.

A political contact with a direct line to Ambassador Mike Huckabee sent him the video of the ambush, explained that I was still in the West Bank, and asked if he would speak with me. He declined.

The Next Day

The next morning, Turmus’ayya’s farmers carried out their first successful olive harvest in more than a year. They credited the viral footage, which had turned into a growing PR crisis for Israel. Soldiers patrolled the fields, and—for once—no settlers attacked or threatened the farmers.

The IDF and Israeli police showed up to conduct an “investigation.” I spotted the soldier who had promised us safe passage before abandoning us with the settlers and confronted him. He and others insisted it was all an accident, that they were very sorry, that they hadn’t known settlers were present, and that of course they cared, otherwise they wouldn’t be there now. What clearly troubled them most, though, was not the attack itself, but my public accusation that they had led us into an ambush—an allegation they said made them look very bad.

Accusing me of spreading propaganda—a day after nearly getting me killed—was a nice touch:

After this, I showed the soldiers two separate videos that flatly contradicted their account—footage of me asking for safe passage and them confirming they’d provide it. Confronted with the evidence, they abruptly changed their line: it was “not our mission to protect you.”

Later, I learned that one settler had, in fact, been present in the olive fields that morning during the so-called investigation: Amishav Melet. Activist Avishay Mohar and journalist Oren Ziv photographed him there and reported that he arrived in a vehicle with an Israeli police officer who was at the scene to “investigate” the attack.

What We Know

To be clear, I have no “smoking gun” proving that the IDF directly colluded with the settlers in the ambush. But here are the facts:

Amishav Melet—the armed, infamously violent leader of the local outpost—spotted us within minutes of leaving for the olive fields that morning, blocking our path and flashing his gun. As he spoke on his phone, more settlers began emerging from the hills behind him.

Melet tracked us through the olive fields and, an hour after we first spotted him, stood beside the Israeli soldiers as they promised us safe passage away from him and the other settlers, back toward the village. Instead, the soldiers sped off in their jeep, leaving us behind with Melet, again on his phone. Minutes later, Melet drove away in his ATV in the same direction as the soldiers, and the lynch mob of armed settlers attacked.

Despite the chaos—screaming, burning vehicles, explosions, and sirens from a Palestinian fire truck echoing across the hills—the IDF didn’t return for more than twenty-four hours.

The next day, Melet arrived at the crime scene with one of the Israeli police officers “investigating” the attack and chatted with them while they collected evidence and interviewed witnesses.

The most generous interpretation is that the soldiers didn’t know dozens of settlers were lying in wait. But even then, they knowingly left us with the armed leader of the outpost after promising safe passage away from him, and failed to respond to the large-scale assault that followed minutes later. Then they returned to the scene with him a day later as though nothing were amiss.

There’s a much more damning interpretation that doesn’t need to be spelled out.

The Days Since

Two days later, at the villagers’ request, I went to the Israeli police station to give a statement to the officer leading the investigation. I walked him through the full timeline and provided extensive photo and video evidence. Still, it was clear his main objective was to establish that I had no definitive proof that the IDF knew the mob was waiting to attack. He kept pressing on whether I could prove the masked men were settlers and not Arabs. I told him I wasn’t going to play that game—that he knew as well as I did who they were—and eventually he dropped it.

At one point, I had to remind him that I was a victim, not a suspect—that his job was to investigate who was responsible for the attack—and that he should consider how he was speaking to me in light of that. He seemed taken aback, as if the thought hadn’t occurred to him before.

For a moment, I thought the public outrage over the footage might force the Israeli police into a token arrest—that they would track down the man with the club, throw him in jail for a week, and pin the entire assault on him. But as the days passed and no arrests were made, I began to doubt that even that would happen.

If the Israeli authorities were serious, there are obvious places to start. Bring in Amishav Melet—already known to the authorities—who was present before, during, and after the attack. Question the soldiers who promised us safe passage and then abandoned us. Interview the police officer who arrived at the scene in Melet’s company.

And if they were truly interested in finding the man who clubbed a defenseless woman, sending her into the ICU with a brain bleed, they could use the same tactics they unleash when hunting Palestinians: gates around every settlement and outpost, checkpoints at every intersection, random settlers stripped, frog-marched, beaten, detained. Smoke him out.

As far as I can tell, none of this has happened.

A week after the ambush, I returned to the scene with a media crew. An IDF jeep rolled up, and according to a Hebrew speaker with us, one soldier looked at me and said to another, “Yeah, that’s him.” They detained me for about thirty minutes, until I got a lawyer on the phone—whatever he said made them drive off without a word. Later, a reliable source informed me that a Telegram group made up of local settlers and soldiers had been circulating my face and name.

In the days since, Melet has remained a fixture in the olive fields, threatening farmers who try to return to their land. On Monday, October 27, when Yaser revisited the site of the ambush with an NBC crew, Melet showed up and told Yaser—and the reporter—that he would “break his face” next time he saw him.

The following day, a convoy of Israeli military jeeps was spotted at Melet’s outpost. Soldiers were seen chatting casually with him. Hours later, he joined them as they tear-gassed a group of farmers and detained several of them. At the police station, Melet was again at their side, pointing out Palestinians he claimed had “thrown rocks” at him.

The scene echoed the killing of Awdah Hathaleen in Umm al-Khair earlier this year, when the shooter—the notorious settler Yinon Levy—was photographed chatting with soldiers afterward, pointing to which Palestinians to arrest. Levy, of course, was never charged. Not long after, settlers built an outpost just meters from the town’s community center, and last week the Israeli government, escorted by the military, issued demolition orders for nearly the entire village.

None of this should come as a surprise. As I’ve written before, these violent settlers are simply doing their job. The most brutal among them are celebrated as “Jewish pioneers,” expanding Israel’s borders, and rewarded by the state with money, weapons, and infrastructure. The settlement project—endorsed at the highest levels of government—is, at its core, a campaign of ethnic cleansing. In this instance, Israel has had no choice but to manage the PR fallout by publicly condemning the attack, but the support runs far deeper than a few choice words.

Up the Chain

A few days ago, an officer from an Israeli intelligence agency contacted me about the case. After consulting with residents of Turmus’ayya and an Israeli attorney who specializes in settler violence, I agreed to meet—if nothing else, everyone felt it was important to provide official documentation to those ostensibly tasked with bringing the attackers to justice.

I can’t share much more, but the agents told me that my footage and its widespread coverage had “seriously shaken things up” at the highest levels of Israel’s security establishment. The local police were no longer in charge, they said—this had become the most intensive investigation of settler terrorism in the region’s history. Even so, I told them I didn’t believe the authorities were truly committed to taking down the terror network in Turmus’ayya. The system investigating these crimes is the same one enabling them.

They assured me they’d prove me wrong. I reminded them that doing so would require more than a few symbolic arrests—it would mean evicting the settlers from Turmus’ayya’s olive fields, dismantling their infrastructure, and ensuring they never return. To this, they had no response.

The Bigger Picture

The story of settler terrorism in the West Bank seems to have broken containment. In Israel, it’s now front-page news in all but the most hardline outlets, and major Western media have picked it up too. I’m glad my documentation helped push it into the spotlight—but to be clear, such attacks happen every day across the West Bank, often with the IDF’s direct backing. The only difference this time was that an American was there to film it.

Israel has responded to all this coverage in predictable fashion—by trying to silence those documenting its crimes. In recent days, it has begun deporting activists.

Still, this whole ordeal has shown that, as impervious as Israel often seems to public criticism, it isn’t. The footage may have brought a brief pause to the violence in Turmus’ayya, but lasting change will require sustained pressure and attention—not only to the violence itself, but to the system that enables it. For my own part, I have no intention of letting this go until real justice is served, and until the people of Turmus’ayya—and the West Bank as a whole—are free to live in peace.

A Moment of Light

I thought I’d end with something nice for a change. A week after the attack, I had the honor of meeting with Um Saleh. She is severely battered, clearly still shell-shocked, and unaccustomed to this spotlight that she certainly never asked for. But towards the end of our meeting, she began to smile a bit. I think she’s starting to realize that she’s become an inspiration to millions, a symbol of Palestinian resilience.

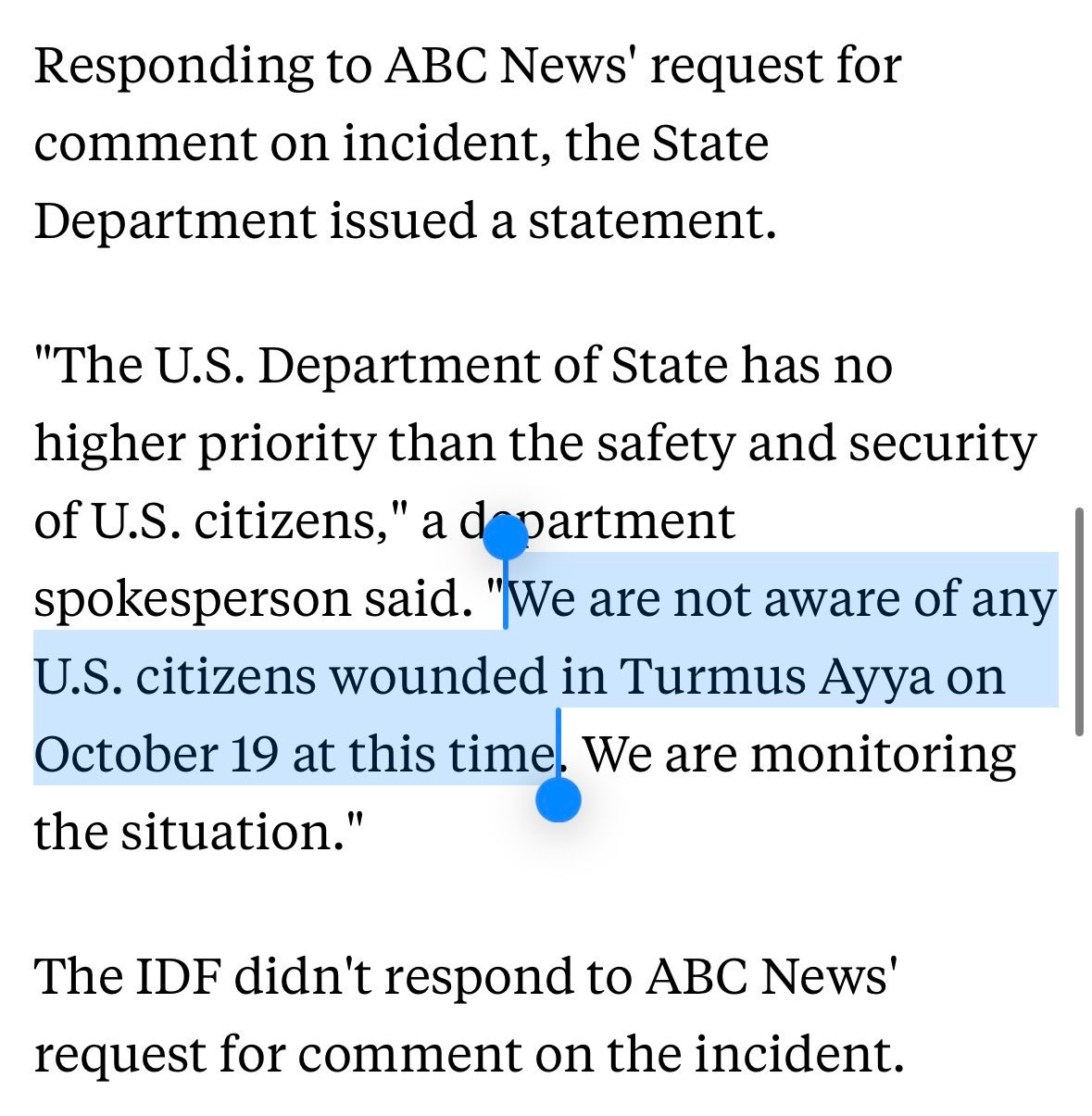

The municipality of Turmus’ayya had reached out a few days earlier to say they were planning a ceremony to honor me and the injured activist, who has chosen to remain anonymous. I told them it wasn’t necessary; I’m just here to document what they live through every day. But they insisted. The worst part of the violence, they explained, was the feeling that it was all happening in darkness—that nobody knew or cared. Now, with their story seen by millions and even raised on the Senate floor, they finally felt the world was watching. They didn’t expect things to change overnight, but they said it had given them hope—something in short supply around here.

So of course I agreed. It was very special. You could feel what it meant to them to be seen, to know their struggle had reached far beyond the village. The kids were especially excited.

I feel a little awkward sharing something like this, but honestly—it’s been a pretty good antidote to feeling powerless all the time.

Consider all this the tip of the iceberg. Much more is coming soon. In the meantime, I’ve been making the podcast rounds. Here are a few recent appearances if you’d like to hear more:

Breaking Points with Krystal Ball and Saagar Enjeti

The Majority Report with Sam Seder and Emma Vigeland

System Update with Glenn Greenwald

Finally, if you haven’t already, please read my story in The Paris Review from last month about the Americans who have been killed by settlers and soldiers in the West Bank—and their families’ futile efforts to find justice in Washington: A Hill To Die On. The Turmus’ayya attack happened just a few kilometers from where several of them were killed and abducted. While I was running that day, one thought kept going through my head: my parents could be on that next trip to D.C.

Note to Readers:

I’ve recently taken the plunge into full-time writing and reporting, leaving behind the work that’s paid my bills for the past fifteen years. It’s both exciting and unnerving—journalism isn’t exactly a gold mine these days, and every bit of my reporting, including this trip, is self-funded. I travel with no crew, no security team—just me. But, at the risk of sounding sentimental, I’ve never felt more certain of my purpose. In the end, this feels less like a decision than an inevitability.

To make this sustainable, I’ll be introducing a paywall soon. If you’d like to lock in the lowest rate, I’m offering 20% off this week—$64 for the year, or $6.40 month-to-month.

It’s tough out here for independent journalists—especially those committed to holding power to account and covering what the mainstream won’t—so your support truly means the world. And as always, I’m grateful when you share this newsletter with others who you think should be reading it.

Also… tomorrow is my birthday.

Thank you,

Jasper

This is so much to process, not in an "I'm overwhelmed" sense but in the sheer machinations of the illegal colonial state to try and obfuscate its crimes. I'm reminded of how Palestinians have been treading this ever-increasingly complicated labyrinth of nonsense and violence for decades. Thank you for this first-person snapshot into how completely insane life has been made for Palestinians and highlighting why we cannot give up the fight on the US side to ending support for Israel. Foot on the gas, friends.

That video of you and Um Saleh was lovely! What a precious being and I'm so glad she is okay.

Happy solar return, sir.

This coverage is ESSENTIAL. Thank you for sharing your truth and the truth of the people of Palestine. May Israel be brought to justice and its leaders shunned by the world